My wife was a preterm baby. From her first breath, she was already exposed to a wide range of health issues that could have debilitated her or, worse, led to her death.

Neonatal sepsis was not among the risks I thought of when she told me her story. Yet, in the minds of many health practitioners, it’s a concern of high priority.

Many preterm neonates have a compromised or even deficient immune system. Microbes can also grow on the devices that help them survive. That leaves pre-term infants more vulnerable to being infected. Inadequate local immune responses then lead to aberrant inflammatory responses in the blood, leading to systemic inflammatory response syndrome. At that point, their chances of dying increase by almost 8% with each hour they’re untreated.

The onset of sepsis leaves a tiny window for clinicians to know whether the preterm infant has sepsis to begin with and what infection led to it. Justin Rolando, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Wyss Institute and Investigator at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, wants to expedite the testing procedure.

He’s identified several biomarkers that can indicate an active neonatal infection in mere hours. For context, it can take days to find an infecting microbe with current methods. His efforts culminated in a major publication that highlights these biomarkers and his procedure.

If you want to hear the story behind these biomarkers and Justin’s plans for expediting the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis, read on.

The Interview

About neonatal sepsis

PN: Your postdoctoral research focuses on neonatal sepsis. What is it and what happens when you leave it untreated?

JR: When disease-causing organisms infect your bloodstream or another location in your body, your body’s immune system fights against it. Sometimes, your body becomes overaggressive while fighting against the infection. When that happens, your body enters a state of sepsis. When this happens to newborns younger than 28 days old, that becomes neonatal sepsis. If the sepsis were left untreated, the infection would grow unchecked. Your baby’s liver, kidneys, and lungs could be irreversibly damaged. Worse yet, the infant could die from organ failure.

PN: Don’t we already have antibiotics to treat blood infections? What complications arise from treating bloodstream infections with antibiotics?

JR: We do have antibiotics that can kill bacteria. However, we must be extra vigilant when using antibiotics. If we overtreat the infant, we expose them to other harm. Most notably, overtreatment disrupts the developing microbiome, increasing the risk of asthma and other allergies. In the worst-case scenario, antibiotics can drive inflammation and the death of bowel tissues at a critical point in an infant’s growth.

PN: In your research, how often do you see infants being overtreated with antibiotics? And what’s causing the trend?

JR: Nearly 90% of all infants were exposed to antibiotics that they didn’t need. Antibiotics are the most prescribed drug in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Yet almost all those infants receive those drugs erroneously and unnecessarily.

I must also clarify that we’re also not wishing to withhold an antibiotic when the infant needs it. That’s why clinicians walk a very tight rope when it comes to treating sepsis. Too little or too much antibiotic is detrimental to the infant’s life and all we want to do is provide the right care at the right time.

New biomarkers in saliva

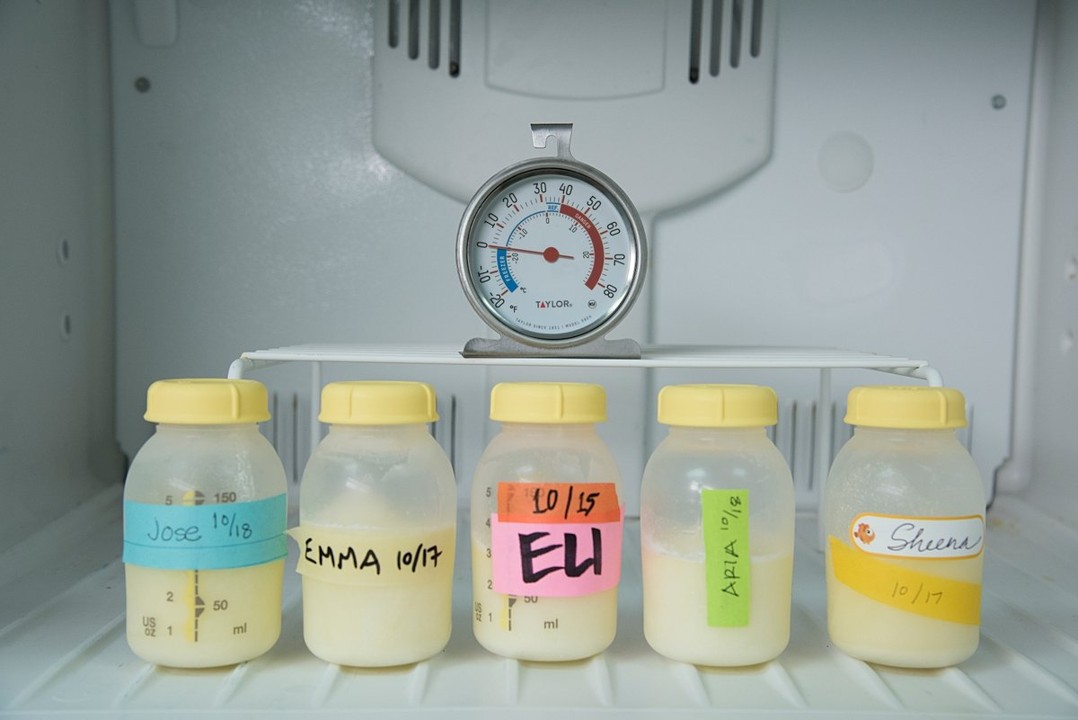

PN: So, how does saliva factor into you balancing on the tightrope that is antibiotic treatment for neonatal sepsis? Aren’t we dealing with a completely different sample type from blood?

JR: At first glance, saliva seems completely unrelated to a bloodstream infection. In reality, saliva is derived from the cell-free fraction of your blood, known as plasma. The salivary glands, the organ that produces saliva in your mouth, secretes that fraction of blood, along with other proteins and enzymes, into the mouth. It’s that trait which makes saliva a surprisingly rich and accessible fluid for monitoring an infant’s blood.

We’re also working with neonates, which confers another advantage for working with saliva. We don’t have to worry about patients having periodontal disease because neonates don’t have teeth. Periodontal disease would create background inflammation levels that make it difficult to distinguish from systemic inflammation. We also have an abundant supply of saliva that we can test. That’s unlike neonatal blood, where taking even a small volume of blood would create substantial health risks for the baby.

PN: You recently leveraged these advantages to identify proteins that could be strong biomarkers of an infection in neonatal sepsis. What are these proteins?

JR: In our published work, we focused on six inflammatory proteins that are associated with an infant’s response to a blood infection. Among those six, we found that two of them — CXCL6 and CCL20 — were significantly elevated among neonatal sepsis patients who had an infection compared with the uninfected neonates. Both proteins are classified as chemokines, a type of protein that directs immune cells to whichever part of the body’s infected.

PN: Our bodies can overreact during a blood infection, leading to sepsis. What happens to these biomarkers in neonatal sepsis?

JR: I’ll start with a normal infant as a reference, here. Their bodies would produce a controlled amount of these proteins to fight the infection. With sepsis, however, their immune responses are dysregulated. Their bodies produce far more of the proteins than needed. That can lead to widespread, uncontrolled inflammation and ultimately organ failure.

PN: Finding out whether a protein’s levels go up in saliva seems much easier than finding bacteria in a blood culture.

JR: That’s the key advantage of our assay. Rather than looking for a specific microbe to know that an infant’s infected, you can look for the protein that indicates infection.

Consider this for a moment. When you’re looking for an infection, you could be looking for a bacterium, a virus, or a fungus. That includes the common Candida family (e.g. Candida auris) of fungal pathogens, more commonly known as yeast. In many cases, these pathogens don’t cause any trouble in a healthy person. But for patients whose immune systems haven’t fully developed — especially the neonates — these infections are deadly.

Many of these organisms can’t be cultured or are notoriously difficult to culture. You could look for the infection with PCR, but you would only be detecting its DNA. That doesn’t indicate whether the infant has a real live infection.

That’s why our test is unique. We’re looking for the host response with these proteins. You wouldn’t need to know where the location is. That’s especially useful because sepsis doesn’t have to originate from the bloodstream. It could come from the urinary tract, brain, or another organ.

Justin's test and its future

PN: How quickly can you perform this test?

JR: It takes about two hours to do without automation. Compare that with blood culture where it takes as long as three days before you see the first signs of bacterial growth. Those days are huge time sinks when you consider that a doctor needs to know whether to administer a broad-spectrum antibiotic or not. With a short two-hour window, the clinician has time to wait before administering an antibiotic. If the results are negative, they don’t need to administer the antibiotic. If the result is positive, they can ask for the blood culture and narrow the spectrum of antibiotics used once they know what pathogen they’re dealing with.

PN: You’re augmenting blood culture’s utility, not replacing it.

JR: Exactly. We want to give the clinician as much actionable information as possible, as quickly as possible. Our test will help doctors feel assured that they aren’t overprescribing antibiotics to patients who don’t need it. In the process, we give them the peace of mind of administering an antibiotic when an infection is likely to be present.

PN: Congratulations on the progress you’ve made with your biomarkers. Where are you hoping to take your biomarkers next?

JR: We’re currently soliciting commercial partners and make our test more accessible in the clinic. More imminently, we’re going to have another manuscript ready in the next few weeks. It details the larger study we’ve done where we assessed our biomarkers from the saliva of thousands of infants. My hope is that with the data we’ve gathered that we’ll gain further investment and support to make our diagnostic test a reality for clinics across the States and eventually the rest of the world.

Author

-

Paul Naphtali is a seasoned online marketing consultant. He brings to the table three years of online marketing and copywriting experience within the life sciences industry. His MSc and PhD experience also provides him with the acumen to understand complex literature and translate it to any audience. This way, he can fulfill his passion for sharing the beauty of biomedical research and inspiring action from his readers.

View all posts