Before the COVID-19 pandemic began, the term “human microbiome” generated a lot of buzz across mainstream media and the academic sphere. Throughout the 2010s, articles like this one from National Geographic and this one from Forbes have highlighted the rise of human microbiome research to better treat a host of human diseases. Amid the talk of the microbes inhabiting the human body, the gut microbiome, in particular, has taken center stage for its links to metabolic health. Changes to the human gut microbiome have been linked with obesity, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and even Type 2 diabetes (T2D). The gut microbiome also shares an axis with other parts of the body that impacts the health of other organs such as the brain. Among these relationships is the gut-liver axis, which establishes a connection between the gut microbiota and liver function.

The gut microbiota and human disease

Now at this point, you’ve probably noticed that I used the terms “microbiome” and “microbiota” in the same paragraph. There is a good reason for that. You see, before we can delve into the microbes that live in your bodies, we need to differentiate between the microbiome and the microbiota. That’s because these two terms have been commonly, yet incorrectly used interchangeably.

- The microbiome represents the genetic material that belongs to the microbes in your bodies. In human microbiome studies, scientists extract DNA from clinical samples (stool, sputum, swabs, etc.) to learn which bacteria they belong to and what functions the DNA encodes.

- Conversely, the microbiota represents the group of living microbes that dwell in your bodies. While the microbiome provides a survey of the microbes living in your bodies, the DNA extracted for these studies can come from dead microbes. Thus, when we talk about the microbes that impact your health, we need to talk about the human microbiota.

Now before we look into the gut-liver axis, any study that uses DNA to characterize microbial communities will be referred to as a gut microbiome study. If the study features live microbes, then I’ll mention the gut microbiota. With that sorted out, we can begin to examine the relationship between the gut and the liver.

What is the gut-liver axis?

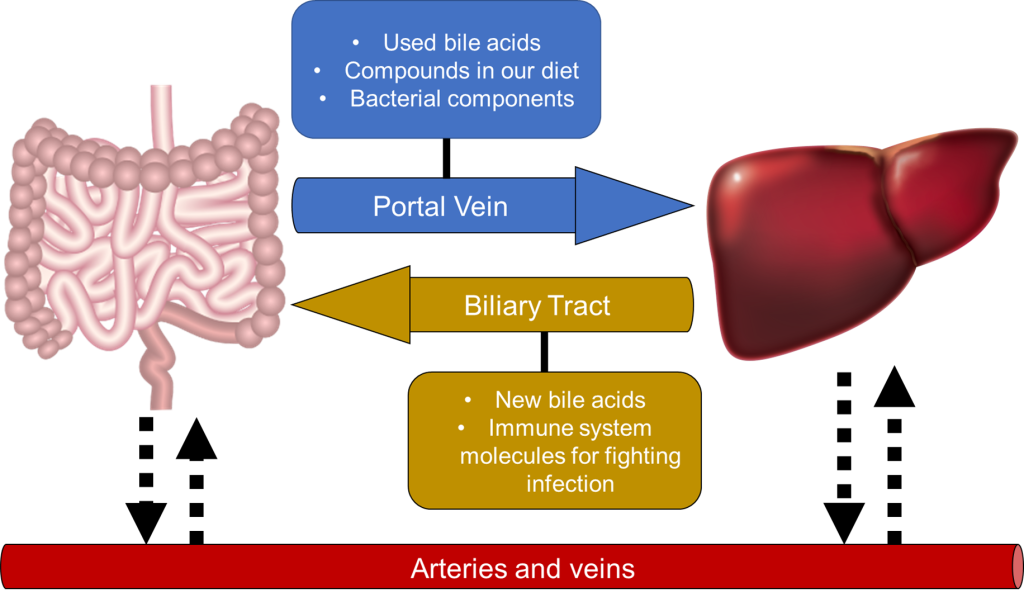

In studies about the human microbiota and microbiome, an axis represents an interaction between two organs that goes both ways. These interactions commonly take place through a series of nerves, blood vessels, or tubes that connect the two organs. With the gut-liver axis, two tubes connect the two organs (Figure 1).

- The portal vein is the first of these tubes. This vein is a blood vessel that connects the large intestine to the liver. It drains blood from the intestines and other organs (ie. spleen, gall bladder, and pancreas) to the liver. The liver filters the blood from the portal vein before bringing it back to the heart. From the intestines, your gut microbes form by-products as they break down any remaining undigested food from the small intestines. These by-products are then diffused into the bloodstream through the portal vein and into the liver.

- The biliary duct helps the liver contribute to the axis by producing compounds that make their way into the large intestines. These compounds, called bile acids, help digest the fats you eat when they enter the small intestine. While the small intestines bring most of the bile acids back into the bloodstream, some of the bile acids can trickle down to the large intestine. Inside the large intestine, gut microbes can digest the bile acids as an energy source. On top of this, the immune system also produces molecules that fight gut infections and maintain liver health through the biliary tract.

- The circulatory system also provides an interface for the intestines and liver to interact in the gut-liver axis. The capillaries – delicate blood vessels smaller than the veins and arteries – transport nutrients and oxygen alongside blood to the intestines from the liver, and vice versa.

The gut microbiota and liver disease

The many ways that the gut and liver can interact with each other enable your gut microbes to impact liver function, and vice versa. With that in mind, what are some ways through which gut bacteria could impact liver health? We may not know for certain right now, but several studies have identified roles that the gut-liver axis can have in driving liver diseases, as seen below:

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a liver disease caused by the buildup of excess fat in the liver. If left inadequately treated, the livers of NAFLD patients can undergo liver inflammation – also known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis (NASH) – and substantial tissue scarring – known as cirrhosis. Both conditions can lead to disease severe enough to require a liver transplant. Obesity is one of the most prominent risk factors for NAFLD, with the prevalence of NAFLD increasing with higher body-mass index values. Changes to the gut microbiome taking place in the guts of obese patients can increase the risk of gut inflammation and damage. This, in turn, enables microbes and microbial toxins to enter and damage the liver through the bloodstream.

- Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) is similar to NAFLD in that fat can accumulate in the liver. However, the difference lies in how the liver is damaged. In ALD, heavy alcohol drinking forces the liver to work harder to produce enzymes that break down the alcohol inside the body. These enzymes induce the production of molecules called reactive oxygen species (ROS) that drive liver damage. With regards to the gut-liver axis, heavy alcohol consumption also encourages bacterial infections in the lymph nodes leading to the liver, contributing to cirrhosis. In a similar fashion as NAFLD, alcohol consumption damages the gut in such a way that microbes and microbial toxins can travel to the liver through the bloodstream.

On top of this, the research on the gut microbiome has suggested changes to the gut microbiota that may play a role in driving liver disease:

- Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a process where patients are administered a fecal solution directly into a patient’s gut to aid gut function. ALD patients with severe liver inflammation who were administered an FMT saw improvements in liver function leading to increased survival in a 12-month period. Mice fed 20-30% ethanol solution also saw changes to their gut microbiomes such as increased abundances of Bacteroidetes and Verrumicrobia and reduced Firmicutes abundance.

- NAFLD patients can also have differences in their gut microbiomes compared with healthy people. For instance, members of Proteobacteria – a group commonly associated with gut diseases – have increased abundance in NAFLD patients with severe liver scarring. Another study identified a higher abundance of Bacteroides and Ruminococcus among NASH patients and liver scarring respectively.

- Patients with cirrhosis can have distinct gut microbiomes from their healthy counterparts. One study determined that there are fewer species in their guts and had higher abundances of two bacterial species, Enterococcus and Peptostreptococcus.

While each of the microbes mentioned have been observed in the human gut, it’s clear that changes in their abundance within the gut microbiome occur alongside liver disease onset. Whether any changes to the gut microbiota cause liver disease or vice versa, however, remains to be seen. Nevertheless, the fact these changes occur raises the possibility that the microbes in your gut play an important role in affecting liver function.

Developing probiotics for treating liver disease

With the literature providing some role of the gut microbiota in liver disease, many biotech companies are ramping up efforts to develop gut-based medicines for slowing down and treating liver diseases. Some of these therapeutics focus on preventing disease by mitigating the causes of liver disease. For instance, Gelesis develops gel-based capsules that work like the fibers you commonly come across in vegetables and whole wheat. When ingested with water, the capsules expand by trapping fluid when they enter the stomach. The expanded capsules make it easier for someone to feel full, aiding weight management.

Biotech companies are also developing two kinds of microbe-based medications for the gut-liver axis (Figure 2). Probiotics, the first of these medications, provide live microorganisms intended to provide health benefits to the person using them. Prebiotics, the other kind of medication, are compounds that enable your gut microbes to grow in such a way that they help your body stay healthy. Multiple companies have already worked on developing both kinds of medications to benefit your gut and liver.

- To develop a probiotic for NAFLD, Novobiome, a France-based biotech startup, launched last year with a bacterial candidate. Classified as a Coriobacteriia, their reduced abundance has been observed among the guts of of NAFLD patients. This probiotic provides a way to mitigate these reductions and help your liver stay healthy.

- Viruses can also act as a probiotic. While we typically associate viruses with human diseases such as COVID-19, a subset of viruses called phages exclusively target bacteria. Phages therefore can be useful for killing a specific bacterium known to cause disease. BiomX, a US-based company, develops phage-based therapies to prevent a dangerous bacterium called Klebsiella pneumoniae from destroying your intestines and driving liver damage.

- MRM Health entered a merger with Dupont Nutrition & Biosciences to develop novel therapeutics for the human microbiota. The company developed a means to simulate the entire GI tract environment from the stomach to the colon. They called this machine the Simulator of the Human Intestinal Microbial Ecosystem (SHIME). The machine lets researchers test how different compounds can impact the gut microbiota under similar growth conditions. By testing different compounds, this effort can help identify existing and novel prebiotics that help prevent or treat liver diseases by using your gut microbes.

Key takeaways

The gut-liver axis represents one of many bi-directional connections featuring your gut. The gut brings nutrients to the liver through the bloodstream, while the liver provides enzymes that help your body digest the food you eat into usable nutrients. Disruptions to this relationship can contribute to liver disease, caused in part by gut damage and exposure to microbes and their toxins in the liver. While research into the role that the gut microbiota plays in liver disease is still evolving, multiple microbial groups have been associated with liver disease progression. This has spurred companies to develop technologies designed to treat liver diseases by harnessing the gut-liver axis. With multiple companies working on prebiotics and probiotics for treating the gut-liver axis, perhaps we’ll be seeing more of these medications hit the market in the near future.

Author

-

Paul Naphtali is a seasoned online marketing consultant. He brings to the table three years of online marketing and copywriting experience within the life sciences industry. His MSc and PhD experience also provides him with the acumen to understand complex literature and translate it to any audience. This way, he can fulfill his passion for sharing the beauty of biomedical research and inspiring action from his readers.

View all posts