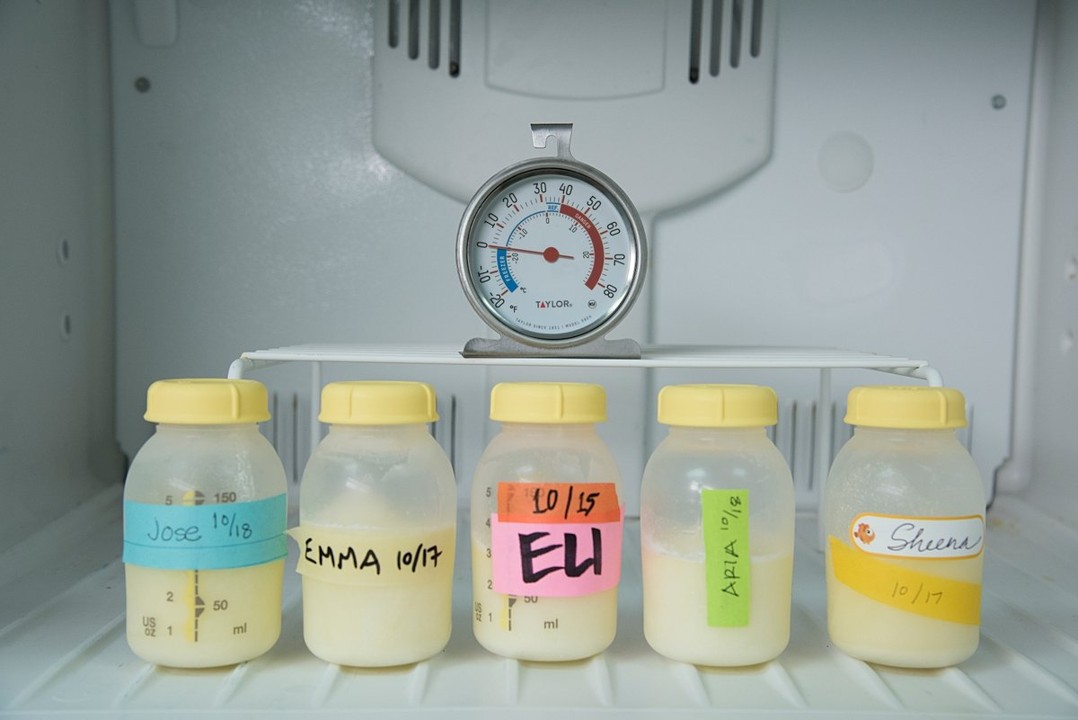

When a mother first produces milk for their newborn, it’s known as colostrum. Personally, I prefer its colloquial equivalent, liquid gold – a dual nod to its yellowish colour and invaluable contents.

In many ways, all of breast milk, even beyond the colostrum, is liquid gold. With so many beneficial compounds and living cells, a baby will receive molecules and cells that they won’t get anywhere else. Each of these components are critical for a baby to grow. The more I reflect on breast milk, the more I realize that breast milk is a mother’s best gift to her baby.

That’s why the WHO has recommended for decades that breastfeeding continue to two years of age and beyond, alongside complementary foods beginning around 6 months. Weaning a baby off breast milk too early deprives the baby of essential nutrients, antibodies, hormones and cells imparted by the mother as they grow. Moreover, we’re now learning that when a baby is weaned too early, they begin acquiring certain bacteria before they’re ready. That leaves them more prone to autoimmune disorders such as asthma.

That’s the kind of finding that Meghan Azad, professor of pediatrics and child health at the University of Manitoba, recently discovered and will explore further through her research.

In today’s interview, we will cover why breastfeeding should be the norm for mothers as they care for their young.

The Interview

Introducing the incredible gift of breast milk

PN: In more ways than one, breast milk is amazing. It’s almost magical how important it is for a baby’s first months of life as you confirmed. What about breast milk makes it so essential for a baby’s immune system to develop properly?

MA: Many things make breast milk a true ‘superfood’ like no other. For one, breast milk contains antibodies produced by the mother. These antibodies fend off dangerous microbes for the growing infant and also help specific beneficial microbes grow in the infant’s gut. The two functions may seem contrasting, but these two ‘sides’ of maternal antibodies complement each other to help the baby grow into a healthy child.

On top of being food, breast milk is an immunological system of its own. Here are just some of the components of human milk we know about:

- Living cells: Human milk delivers beneficial microbes and maternal immune cells. These cells further bolster an infant’s immune system as they grow.

- Antimicrobial compounds: Proteins and enzymes such as lactoferrin and lysozyme can also kill pathogens and prevent dangerous microbes from colonizing the gut.

- Other immune system proteins: Other immune system compounds such as cytokines and chemokines also give the baby a first line of defense against pathogens while the immune system develops. As the baby’s immune system matures, they depend on their mother’s milk to obtain antibodies.

These components act locally in the infant gut, and some are also absorbed into the infant’s circulation, together they educate the infant immune system to provide protection from disease without ‘overreacting’ (which can lead to allergies and other autoimmune conditions). What’s even more amazing about breast milk is that its composition is dynamic. It changes across feeds and over time to match developmental needs and environmental conditions.

PN: Your research focuses on the bacteria that teem in our guts, known as the gut microbiome. How does a baby drinking breast milk benefit its gut microbiome?

MA: Breast milk contains a special type of carbohydrate: oligosaccharides. These molecules are polymers of three to ten sugar molecules long, with dozens of possible structures and combinations that vary among mothers. These oligosaccharides are not digested by the baby but instead serve as food for specific beneficial gut microbes.

PN: Our discussion so far has delved into the molecules and organisms that comprise breast milk. Have we captured all of it yet? If we haven’t what’s the best way to uncover the rest of the molecules and their role in infant health?

MA: We know a lot about breast milk composition thanks to a combination of targeted and untargeted methods. Targeted methods quantify molecules and proteins we already know about. Conversely, untargeted methods help us discover new compounds by profiling the entire set of compounds present in a sample – including many that might not yet have known identities.

From Manitoba, with funding from the Gates Foundation, we created the International Milk Composition (iMiC) Consortium to learn about these molecules. We’ve teamed up with researchers in Pakistan, Burkina Faso, Tanzania and the USA and used powerful techniques to analyze breast milk from over 1000 mothers across 4 continents. In the process, we detected thousands of peptides, metabolites, and microbes. As we decipher their identities, we’re planning lab experiments with cellular and animal models to figure out what these compounds do in the growing infant. By combining targeted and untargeted approaches, we’re making key discoveries about the role of breast milk in an infant’s long-term health.

Breast milk and infant respiratory health: a new connection

PN: This is a perfect segue into the core of your study. In it, you developed a machine learning tool to predict whether a child will have asthma based in part on when the child was breastfed. How does it work, and what were the most important factors?

MA: The beauty of machine learning lies in its ability to track hundreds of variables at once over time. In the Canadian CHILD Cohort, we tracked more than 2000 infants for three years from birth to see which early-life factors could predict asthma development. We tested 132 variables in all, focusing on microbes and milk components, to see which of them would best predict asthma.

From the microbiome side, we observed that just taking a single snapshot of the gut microbiome wasn’t a great predictor; we could only correctly predict asthma 55-65% of the time. However, when we modeled how the microbiome changed between 3 months and 1 year, the predictions were much stronger, with accuracy jumping up to 80-90%.

We learned that when a microbe first arrived in the gut made all the difference. One such microbe, Ruminococcus gnavus, appeared to be harmful when acquired too early, but protective when it came later. We saw a similar trend for other late colonizers such as Streptococcus salivarius, Dolosigranulum, and Moraxella.

PN: Given how important breast milk is to an infant’s health, did including the components of breast milk into your models improve your predictions?

MA: Certainly. We saw that factors found in mothers’ milk contributed to healthy respiratory development. IgA, specific oligosaccharides, and fatty acids were some of the components we found to be predictive. Considering these breast milk components revealed that breastfeeding supports well-paced colonization of the nasal and gut microbiomes, which in turn protects against asthma. Conversely, we found that early weaning triggers premature diversification of these microbiomes, which increases asthma risk.

PN: What do you think is going on to link premature microbial acquisition with asthma risk for infants?

MA: The key to what we found is that it’s not just about which microbes infants acquire. When they arrive also shapes asthma risk. When infants stopped breastfeeding too early, they experienced what we call a “premature weaning reaction.” Microbes typically found in adults were found in the infant gut months before the baby’s immune system was ready for them. This mistiming disrupted normal immune training: for example, early arrival of microbial functions like tryptophan metabolism and mucin degradation likely skewed immune signaling toward inflammation instead of tolerance. In contrast, gradual, well-paced colonization — microbes arriving in the right order at the right time — supported balanced immune development and reduced asthma risk. Timing is everything!

Ending with advice for breastfeeding mothers

PN: With how important timing can be, why do you think mothers wean their children off breast milk prematurely? How can we address those reasons?

MA: Infant feeding decisions are personal and complex – but research shows that many mothers stop breastfeeding before they are ready. Often this is related to breastfeeding difficulties, such as pain, latch issues, or low milk supply – which can all be addressed with proper support. Other reasons include societal barriers that we need to work towards removing, such as the stigma around public breastfeeding and structural barriers in the workplace.

Supporting families to meet their breastfeeding goals should be a top public health priority. Strong individual and family-level supports are essential for this. We need to make early hands-on clinical support available for all new parents and provide clear guidance, so that ‘low supply’ is not overdiagnosed. As well, workplace policies need to uphold and protect time and space for breastfeeding or pumping. We should also encourage paid parental leave and promote non-judgmental, evidence-based learning for kids, parents and healthcare providers.

PN: There’s a lot we can do to support mothers, especially when it comes to breastfeeding difficulties. In fact, I know a few mothers who struggle to produce enough breast milk for their babies.

MA: It’s often possible to increase supply – strategic pumping can help, and seeing a professional lactation consultant or breastfeeding medicine specialist can be a game changer. It may be possible to identify a reason and treat the root cause with medication. But even if supply remains limited and supplementation is necessary, there is huge benefit to ANY amount of mother’s milk. Our research shows a ‘dose response’ – meaning every bit counts, and any amount is beneficial.

Author

-

Paul Naphtali is a seasoned online marketing consultant. He brings to the table three years of online marketing and copywriting experience within the life sciences industry. His MSc and PhD experience also provides him with the acumen to understand complex literature and translate it to any audience. This way, he can fulfill his passion for sharing the beauty of biomedical research and inspiring action from his readers.

View all posts